|

I wrote this post eight years ago today. It came to my mind tonight, when I burst into tears at the dinner table and one of my sons asked me why I'm crying. I'm crying because this is what I do this time of the night on this particular day of the year. I don't pray the same now as I did in this post, but I grieve the same.

I love you, Dad. --- This post could just as easily have been called Death. Or Discretion. It's the 7th anniversary of my dad's death today, and all three titles would have taken me in fruitful reflective directions. "Dad" is, of course, the sunny member of the triad, with Death still my enemy and Discretion too much of a preaching topic in this in-your-face-with-my-feelings Facebook world in which we live. Not to mention discretion eludes me at the moment. So, Dad. Dad! I never expect to get upset just writing the name I called him, and yet here I am tearing up as I type. It catches me off guard because seven years into the journey, Dad functions in my life mostly as memory. With exceptions like this, when by the grace and severe mercy of God Dad is resurrected, if only for a few seconds. Also in dreams when I see him and always know I don't have much time left before he'll leave. And listening to Art Garfunkel or Cat Stevens when "Barbara Allen" or "Morning Has Broken" come on. Or when a new baby is born in our family (and two have been in the past two months) and Dad seems around (or perhaps more accurately, the painful insufficiency of Dad as memory is made clear, and I wonder what he can see where he is, on the other side). In a way Dad is always resurrected at this time of year, which makes sense. His death anniversary never sneaks up on me, thanks to his cancer journey lasting only 16 days. January 31-February 15 is something like my family's Holy Week, our (two) week journey to the cross. Normal life gets invaded by stark Dad memories, so real I almost forget where I am. Sunday night I was with my kids in the nursery at church and suddenly I was also with the rest of my family around Dad's hospital bed, hearing him courageously agree to the Do Not Resuscitate options. I won't tell you how he looked, just that I saw it, like I was there. This afternoon I was on the playground watching my kids and it happened again. Suddenly I was also in the hospital, in the ICU waiting room during the nurse's shift change when my Dad died. I wasn't with him when it happened. I was just outside, with my sister and brother and about 20 of our relatives, but they didn't get us there in time. Dad was still waiting for the ice cream he had asked for and we were cordoned outside of the unit while the nurses changed shifts. And just like that his time was up and he died, no ice cream, no good-byes, just a last breath for which only my mom was present. For a long time I was haunted by what he looked like in death, but I can honestly say I don't remember anymore, and I am thankful to have forgotten. I prayed to forget. But wait, I was supposed to be talking about resurrection. You'll have to excuse me, this always happens. The evening, the 7:29pm as I stare at the clock. It was around now, and every year it hits me around now, after dinner, because it was after dinner that Dad died. We had our Last Supper in the hospital cafeteria while Dad lay upstairs in his hospital bed. Only there was no betrayal, no bitterness, simply the cancer and Dad and an It Is Finished. Finished at 47 years and four months, and I want to wave that in everyone's face every time they ask how long it has been since he's gone. Seven years gone but he was only 47 (blippety-blip) years old. I want to say it, but I don't. That's where discretion comes in. And for my money, grief is the best teacher of discretion there is. Because you cannot and should not say everything that comes into your mind, not even when you are in pain, not even when the best dad in the world dies. And if you can learn not to say everything and anything that comes into your mind in those circumstances, discretion during the less painful parts of life is a walk in the park. Dad taught me that too, now that I think about it. Dad chose his words, chose when to speak, and usually chose well. Seven years after he's gone, I remember it again. Three days ago I prayed through all of this, in my journal, sitting in the nursery. I don't usually share my written prayers, but it would be ridiculous to talk about losing Dad without ending in prayer. It always ends there; it has to end there. God is the great exception to my discretion, the One to whom I turned when Dad died and the One who has faithfully borne me up and borne with my anger and my coveting when I see other people's fathers alive and want mine to be too. So here is that record, a prayer prayed three days before this strange anniversary: Thank You, Lord, for my dad. Thank You again for the 47 years of his life and the 25 of my own that I was privileged to be his daughter. Thank you that though I remember some things, that memory of Dad in death has been erased--as I prayed it would, though I didn't believe it possible. Thank you that Dad's cancer journey was short. Thank you for the thousand consolations that have come since his death, not the least of which is the Good News of the resurrection for all who believe. And that Dad did believe. I thank you for that. You are my deepest solace, my comfort and my stronghold. Who would I be without You? You are my everything. You are my peace, my joy, my hope, my everything. I love You, Abba. And please let my dad know I love and miss him too. Your, Kadee

2 Comments

When I was eight months pregnant with my fourth and final child, my husband and I faced the possibility of overstaying our permits here in Canada. We had applied for permanent residency months before, but were delayed because I needed medical clearance in the form of an X-ray proving I didn’t have tuberculosis. The technicians in Canada understandably refused to give X-rays to pregnant women. So we had to wait for clearance until our daughter was born, and she wasn’t due until two weeks after our permits expired–at which point our legal right to be in the country ended.

Eager to avoid this, we went in person down to the border to plead with Canadian immigration officials for a temporary extension of our permits. Normally we would just mail in that kind of request, but we thought my huge, pregnant belly would help them understand the urgency of having our permits right away. Instead, we got a lecture from the border officials on trying to circumvent the immigration system and we were sent home to apply online. We lived on the hope that whoever opened our application thousands of kilometers from where we lived would believe it was okay for us to stay. It’s hard to appreciate the peace of mind in knowing you can stay in the country that has become your home until that peace of mind is threatened. It’s hard to understand how devastating an involuntary departure can be until you are facing it yourself. I have listened from across the border to the immigration debate in my home country of America. And I’ve been struck by the–apathy? Impatience?–some of my fellow citizens have towards non-citizens trying to make a home there. It feels like those arguing against amnesty or in favour of harsher immigration laws treat their own natural-born citizenship as some kind of personal accomplishment. As if they or their ancestors deserved to be here in ways that someone now trying to seek entry does not. Read the rest over at The Wisdom Daily. Entertaining Angels: Lessons People Outside My Religious Community Have Taught Me on Faith5/22/2019 When we were young and foolish, my now-husband and I (along with another friend) spent a weekend hitchhiking through northern Israel. We were spending a semester abroad there and made up our minds to see more of the Galilee and Golan Heights than our class field trips would allow. It was one year before the second intifada and two years before 9/11. Looking back, I know we were privy to a peaceful season, a thin sliver of the young country’s history when things were exceptionally calm.

So many people picked us up and gave us rides in our weekend trip. One was a dairy farmer from a nearby moshav who knew my hometown of 4000 people (and many more cows) because he had visited it to improve their own dairy methods. Another was a thoughtful, articulate guy with red hair and a nice car who talked to us about the plausibility of a peace deal. The most memorable ride wasn’t really a ride at all. A small truck filled with Russian-speaking men passed us several times as we were making our way to a nature reserve. The last time they passed, we watched in wonder as they stopped at the top of a hill and backed slowly down to where we were standing. The men piled out–the oldest couldn’t have been more than 25–and opened the back of the truck to show us huge bunches of bananas. With hand gestures and broken Hebrew, they let us know they couldn’t give us a ride but didn’t want to be unhelpful. And then they pushed bananas into our hands, took a picture with us, and climbed back into the truck and driving off... Read the rest over at The Wisdom Daily. Last week the United Methodist Church, a sister denomination to my own, voted to reject a “big tent” proposal that would allow those clergy and congregations who fully affirm their LGBTQ brothers and sisters to remain in communion with those who do not. For those who hold traditional, non-affirming positions on the subject, the vote was hailed as a victory. For those on the other side (if sides there must be), it was a day of heartbreak and grief.

A month earlier, my own denomination–which is non-affirming in that it officially does not allow LGBTQ people to hold positions of church leadership–reissued its own statement on the sanctity of all human life. This came in response to a set of American laws recently passed; not on the rights of LGBTQ people, but on abortion. As a denomination we condemn abortion because, in our view, abortion involves the termination of life; life that is valuable to God and, therefore, valuable to us. In the confluence of these two decisions I wonder: why don’t we evaluate our doctrines on gender and sexuality through the same lens with which we evaluate abortion? What if our theological perspective on our LGBTQ brothers and sisters was filtered through an affirmation of the sanctity of life and its corresponding repudiation of practices that lead to death? Read the rest over at The Wisdom Daily. When my dad died 14 years ago at the age of 47, my family instinctively knew how to spend the first few days: making funeral arrangements, contacting friends and family, picking a burial spot, and gathering with hundreds of people in a church to say a formal goodbye.

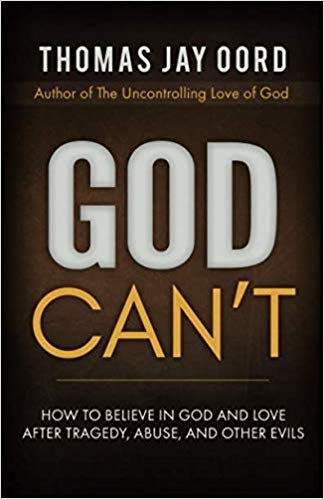

It was after that first week that grief became a tumble in the dark. When we–my brother, sister, and I–said good-bye to our mother and returned to our respective homes, we did so with hearts torn and little direction. Not so long ago, people like us would have worn black for a year to give everyone else a clue that we were mourning, but neither our cultural, nor faith traditions have such concrete practices in place now. Modern life, for better and worse, doesn’t allow for public declarations... To read the rest, head to The Wisdom Daily. Book Review: "God Can't: How to Believe in God and Love After Tragedy, Abuse and Other Evils1/24/2019  There are few areas in Christian life that demand responsible theological response more than the experience of evil and tragedy. In my experience, both as a pastor and trauma survivor, those same situations act as a magnet to harmful, faith-killing responses based on theology that places responsibility for trauma or tragedy firmly in the hands of God. I was happily surprised and deeply moved by the perspective offered in Dr. Thomas Jay Oord’s newest book “God Can’t: How to Believe in God and Love After Tragedy, Abuse, and Other Evils”. Oord’s theology on God’s character and the reality of evil is laid out in five compassionate, articulately written and universally accessible chapters, each one concluding with reflective questions that will help groups and individuals process what they have just read. From the beginning, Oord makes clear that the individual doctrine outlined in each chapter is interdependent on the other four. The most central of these doctrines is, in my view, the first: God Can’t Prevent Evil. It is based on the theological assumption that the love of God is inherently uncontrolling, a statement expounded on more fully in Oord’s previous works. If we believe, as Oord argues, that a love that controls is not really love, than control even in cases of evil becomes impossible because it is against the nature of the God who is love. Oord’s insistence that God CAN’T control will (as he himself admits) be incredibly unsettling to many readers. I think many Christians have seasons when we need desperately to relax into the arms of a God who tells the waves when to crest and the birds when to fly. But framing the impossibility of control in terms of God’s loving nature makes it, for me, a persuasive argument. Oord reviews more traditional perspectives based on a belief in God’s omnipotence (God controls everything, God chooses to control some people/situations but not others, etc.) and is honest about their strengths and weaknesses. The alternative he offers is striking: asking how far the love of God goes, and whether a love that could act to prevent evil and doesn’t is really love at all. (The answer is a resounding no). The remaining four chapters lay out four theological statements that strengthen or refine the first: God Feels Our Pain, God Works to Heal, God Squeezes Good from Bad, and God Needs Our Cooperation. In addition to providing Scriptural and theological support for each statement, Oord includes the stories of individuals who have experienced trauma and tragedy and found conventional theological explanations unhelpful or even harmful. As both a pastor and parishioner, I’ve heard myriad ways in which people make sense of tragedy. Many do so by attributing it to the will of God, focusing on the mystery of His ways to manage more troubling thoughts about the divine choice to harm. While I would not presume to tell a survivor how to make their peace with God, I think many would benefit from the opportunity to consider another option: one in which God neither sent the harm nor stood by and allowed it to take place when He could have done otherwise. While “God Can’t” is of special value to those currently wrestling with questions of God’s goodness, I believe it’s an equally valuable addition to the shelves of all who profess faith in Christ. What we believe about God’s intervention--or lack thereof--in the circumstances of our lives impacts what we say and how we respond to our friends, our family, and our communities at large when tragedy strikes. I am still questioning and processing several statements in the book, and likely will for some time. There are a few points of biblical interpretation that I question; stories in the Old and New Testament that, in my view, beg particular assumptions of the book. But the overarching perspective has succeeded in gathering the fragments of my heart, the wounded parts that view God with mistrust. I think that is why I found myself brought to tears as I read. The doctrine of the omnipotence of God, however loosely I held it, has nonetheless wielded great power over me as I have processed trauma and tragedy in my own life. To be given the glimpse of an alternative--one that keeps the Trinitarian Father, Son, and Spirit but refuses to put a whip in that God’s hands--has been powerful and healing in and of itself. Note: This was originally posted on November 27, 2016

Dear God, I need Advent. I need the lights flickering in the darkness, the purple and pink against the wreath of green. I need the swollen belly of Mother Mary, her patient, jubilant waiting for a baby she didn't plan, for the conclusion of a pregnancy she never foresaw but nonetheless saw through. I need the Eternal, flesh-and-blood beacon of hope to clear my glassy-eyed view of a world I both know and no longer recognize. Dear God, I need Advent. ----- Dear Jesus, I need Advent. I need the creeping, humbling movement towards Your birth; the steady, unfaltering flow towards a life beginning and ending in a human cry. I need the jubilance of Aunt Elizabeth, the kicking fancy of Your cousin John in her womb as he heard Your mother enter their home. I need the striking, steely confidence of peasants in Nazareth and Bethlehem and Judea; the assurance that You, O Son of God and God-With-Us, lived your 33 years among the poorest of the poor. I need the reminder that You were shielded and cared for by the humble time and time again when You, Infant Lowly, could not shield or care for Yourself. Dear Jesus, I need Advent. ----- Dear friends, I need Advent. I need the breathless, despair-battling waits on nights that fall too early and last too long. I need the glorious anticipation of a Redeemer come down to earth, nurtured and grown in the belly of a Woman like me, a Woman whose courage encourages me. I need the company of shepherds and angels. I need the exquisite yearning that arises in counting down the weeks until I join an eternal choir that declares "Glory to God in the highest!" I need the Divine descent to incarnation that I, and all of my [human] race, might be raised up. I need Advent with every fibre of my being. And, thank God, Advent is here.

(Originally posted in 2012. Even truer today).

My plan in this alphabetically-inspired series was to write a post about the boys and man in my life when it came time for their name-letters. But since I'm planning to cover the M with Modesty (such fun!), which will usurp my husband's name (Matt), I'm opting to write about him here, under the L. Love. It works too. Love is the beginning and the end to my thoughts on Matt. I fell in love with Matt in Israel. [Yes, Israel]. We were both there as American students studying abroad, along with about 100 other remarkable people from all over the United States and a few other spots around the world. We met in Jerusalem, where our school was, but I'm not sure if that's exactly where the "in love" came about. I know that I started to fall in love with him in Ein Gedi, hiking through the oases near the Dead Sea. And I know I was definitely in love by the time we went to Galilee a few weeks later. Where it happened between those two places I can't say for sure, but it was probably Jerusalem (and that's not too shabby of a spot, you know)? As luck would have it, Matt came to Jerusalem already in a relationship, while I was very single. I blame those details for why it took so long for me to realize what an incredible guy he was. But once I started to clue in, it was a quick free fall on my side into in-love-ness. Matt was so patient. So wise. So compassionate and interesting and so terribly good looking! I knew, very quickly, that he was, if not the guy I'd been looking for, exactly the kind of guy I should be looking for. And I was more inclined to think it was the former, not the latter. I never said a word about how I felt while we were in Israel out of respect for his relationship. But after we got back, I got an e-mail from Matt a week or so later indicating the relationship was over. And, maybe 48 hours later, I wrote to let him know that I was in love with him. Because I was crazy. Love is crazy sometimes. As it turned out, he was in love with me, too. And so we committed ourselves to each other, despite being 3000 miles apart, despite being precisely at the stage in life when everyone is most suspicious about such commitments working out. We spent the next year and a half apart, completing our degrees at our respective universities. We visited each other every 2-3 months (with one four-month period in which our physical separation, my burgeoning feminism, and mutual communication catastrophes almost ended everything). After graduation I went off to Central Asia for the summer as part of an internship, and Matt (brave man that he is) went to my parents' home for the summer to work for my dad. I came back from Central Asia in early August for my twin sister's wedding. And three days later, Matt asked me to marry him with a beautiful ring and a bottle of Israeli wine in tow. Looking back, it seems a bit crazy. We had spent such (relatively) little time together. But love is crazy sometimes. We got married after being engaged for 2 1/2 months, hurried along by our impending entrance into graduate school. About a month after that we moved to Kansas City for what was one of the most difficult 1 1/2 years of my life. Kansas City didn't agree with either one of us, and the first year of marriage is a bruiser anyways. We had gone there on my lead, and though Matt never said he resented me for it, I resented myself. It just plain wasn't working, and we doubted it ever would. A few friends of ours were at Regent College in Vancouver and loving it, so we looked into going there instead. And decided, together, to go. As I've written about before, I got pregnant with Isaac after we were already full-steam ahead in our plans to move. Knowing I would give birth after just one semester, I expected that Matt would be the full-time student and I would postpone my studies. But when we talked about it, Matt suggested exactly the opposite. He would start part-time, I would start full-time, and we would see how it worked out from there. How it worked out from there is that I completed my Master's degree and Matt didn't. He still hasn't. I don't think he knew that it would be so when he first made the decision, but we both realized quickly that it would likely mean just that. He gave up his education for mine. He worked full-time to pay for my schooling. He took care of our sons on the evenings and weekends so I could keep up my studies. And in all that, he never faltered or bemoaned the cost (and it cost a lot, emotionally as well as financially). He supported me in school and ministry through four years of graduate school until I finally got my degree. Looking back, it seems a bit crazy. Matt could have insisted I postpone my degree until he finished his, and I would have done it. He could have, at any point, persuaded me that too much was required of him for my education's sake, that he was doing all the giving with none of the getting. I am amazed actually, looking back, that he didn't do just that. Except that I know, 12 years now into being in love with him, that it's the kind of man he is. It's the kind of man I sensed he was in Ein Gedi, in Galilee, in Jerusalem. I sensed he was patient, and he is. I sensed he was faithful and persevering, and he is. And it means all the more to me now, for I know now that not all men turn out to be the kind of men we first think they are. Sometimes the ones who seem best are simply the ones putting on the best show. I take it as grace--completely undeserved--that Matt was the real deal. Matt is the real deal. He was and is worthy of my love. And I am working, for the rest of my life, on being worthy of his. I was holding my palm leaves Sunday, Lord, waving them and singing as my daughter marched around the sanctuary. She held a tambourine and had friends to follow, so she let fly her normal self-consciousness and bounced on the downbeat while we in the pews sang. She didn't know what she was celebrating. But then, how many in the crowds did that day so long ago? It was a desperately beautiful thing to be able to celebrate at all. My morning before the service was spent reading about and mourning the deaths of worshippers in Alexandria and Tanta. Our Egyptian brothers and sisters gathered with their palms just as we did on the other side of the world; they chanted, they praised, they prayed. Why were they killed on a day of such joy? ----- There is an ugly appropriateness to the timing, if we look for such things. You set Your face against the night by entering the Holy City as a king on Palm Sunday, but Your departure five days later was on the terms of the violent and powerful and afraid. Our brothers and sisters in Egypt have long known persecution, but year after year they choose to enter their sanctuaries for worship. This year, like You, they departed on terms not of their choosing. Here I am again, staring down the age-old cruciform paradox: I will never look comfortably at You beating a path of suffering and calling Your disciples to follow You. The cross still disgusts and terrifies me. And yet, I will never cease thanksgiving that in being lifted up to death, You set Yourself eternally on the side of victims of violence. O Lord of Tanta and Alexandria, of Aleppo and Sana'a, have mercy on us. O Lord of Tanta and Alexandria, of Aleppo and Sana'a, teach us to walk in Your ways. ----- Why did they, and why do we, show up Sunday after Sunday, year after year? Do You know, Lord, I haven't been stopped asking that question over this past awful year and a half? What's it all for, this gathering and singing and eating and departing? Haven't we better things to do, better places to be, better ways to spend our time? The question lingers, growing or shrinking in intensity. Sometimes I go to church with my family. Sometimes I stay home alone. And yet I was discomfited and disoriented when I realized I might have to miss the service this past week. Of all Sundays, I wanted to be at church the day we wave the palms. Of all Sundays, I wanted my kids to be at church the day they march up the aisles with their tambourines and palm branches shouting, "Hosanna!" Religious-born PTSD means most superficialities have been killed off. The spectacle isn't enough to draw me to church anymore, and I no longer have a job that requires me to be in the pew. My reasons for going on Palm Sunday were simpler, more body and home than anything else. I wanted to be with the people who recognize You as king. I wanted my children to wave the palms with the communion of saints who choose century after century the Way that leads through Jerusalem. ----- I still puzzle over why we go to this place or that, with this people or that people to find You, to worship You. Some days the answers I "know” as a Christian and ordained person do not suffice. There are things I will never believe again this side of exile, and things I never want to believe again. My brother Peter asked You once, "To whom can we go?" when You knew some of Your disciples weren't sure they could follow You anymore. I used to feel his certainty, but I know now that there are other places to go, other paths to take. I could walk away from a life of faith altogether. I have dropped it several times like a scalding pot only to pick it up again when I trust it is safe to do so. I could abandon the faith in which I was raised and choose to practice a different one. I have looked elsewhere these past 19 months, scanning my eyes over different faiths and no faiths and everything in between. There are many ways of seeking and living what is good and right and true. But both of these require the one thing I know now I can’t do: I can’t leave You behind. And since I cannot leave You, nor even wish to, it seems far better to learn again how to walk with You. You, Jesus, who rode into the Holy City accepting the part given you with its glory and ridicule. You who washed the feet of your disciples like a mother scrubbing up her young. You who broke bread and poured wine and drank the cup of bitter abandonment. You who dared to love when love lay down with betrayal and delivered you to death. You who rose as its Conqueror. I walk beside You, carefully, cautiously, a bit fearfully. As Your people have from Jerusalem to Alexandria and Tanta and beyond. And yes, we are afraid. But You are with us. And where You are is where we want to be. I had forgotten. That is my confession and my creed. I had forgotten how lost and alone I was when, seventeen years ago, I boarded a plane with a friend to travel halfway around the world to study in Israel for a semester. I had forgotten how wounded I was upon leaving, how the previous year's hurts and disappointments had shattered my sense of security and suffocated my sense of God. I had forgotten how, upon arriving, that lostness and aloneness remained for such a very short time because I was so quickly absorbed by and healed within a community of good and decent people. I had forgotten how far God seemed from me for the first month or two. How I, as a student of religion, had in many ways reduced God to a topic of conversation; an endless Object of speculation and cynicism given begrudging respect, and always at a distance. I had forgotten how one night God came near. How one minute I was studying Hebrew and the next I was stunned and overwhelmed by the depth of my need for Him. And not only of my need, but the vastness of His love for me. I had forgotten what it was to be lost and then found, and to know that even "lost" is a matter of perspective--how He had never misplaced or overlooked me, however much I had felt it to be so. I had forgotten what it meant to be brought to life in the company of people who took God seriously. What it meant to know that those who prayed at the dinner table also sought God in the morning and at night. I had forgotten what it was for a 20-year-old woman to be gently and in some ways unknowingly directed towards God by peers who gently but knowingly practiced their faith in Him with kindness and wisdom and joy. I had forgotten what it was to walk the ancient stone city and be spoken to not so much by the religious sites but by the faith lived out by flesh-and-blood women and men. I had forgotten what it was to be surrounded by the humble faithful, to have my cynicism and criticism quieted by respectful, wholehearted adoration of the God of Abraham, Isaac, and Jacob. I had forgotten what it was to meet Jesus in the beauty of the land where He grew up; where He healed, where He preached. The sacred sites themselves did not engender intimacy with Him, as it did and does with others. But sitting on the water's edge and hearing the light lapping of the Sea against the shore--that drew me near to the fishing, walking, calling Saviour Who chose this place to spend most of his three years of public ministry. I had forgotten all of these things, and for nine beautiful days I learned again how to remember. I walked the same places, and was overwhelmed at times by memories of beloved people, so powerful they seemed at times to be resurrected to the present. But of course, they weren't. Apart from my husband, the people who had helped form my faith and made Jerusalem home weren't with me and it was the past that seemed so alive, not the present. There was always the temptation to sink back in the past; to revel in it and treasure it to the point that the present seemed a shadow, a step backwards, a disappointment. There was only one good Way to go: forward. Allowing and acknowledging grief that the precious season of my life, 17 years ago is over and, simultaneously, to open my heart in deep and endless gratitude. Gratitude for the time I had with the beautiful people who shared it with me (including the man who has shared everything with me since). Gratitude for the time I had now, as a proper adult and mother of four, to revisit a place of such joy and remember and learn again why it had been so. ----- It is enough. It is more than enough. Whatever uncertain, disquieting questions linger about my life at this stage, I know what I have been given, and it is enough. I remember now what I had forgotten: the richness of people and places and nourishment God has given me along the Way, particularly for those precious, powerful three and a half months in 1999 when I fell in love with Him. I don't need to recreate it. It is enough to know that it was, and enough to know that He was, and is, and will be. |

Archives

February 2020

Categories |

RSS Feed

RSS Feed